Mercenary Nation

From the trenches of Ukraine to the dunes of Darfur, Colombians have become a global fixture in modern conflicts.

The nation of Colombia is quickly gaining notoriety for a new type of illicit global export – one that makes its presence known in the trenches of Eastern Ukraine and the refugee camps of Sudan rather than in the nightclubs of Manhattan.

Colombian mercenaries are appearing everywhere. Over the last year, abundant evidence has emerged of their involvement in the Ukraine conflict – on both sides – and in the ranks of the Sudanese Rapid Support Forces, who are waging a brutal campaign of ethnic annihilation in Darfur.

Additionally, reports have surfaced of Colombian ‘security contractors’ supporting drug cartel operations in Mexico and government-backed militias in Eastern Congo. The rise of this phenomenon was put on dramatic display in 2021, when 26 Colombian contractors were arrested for allegedly assassinating the Haitian President, plunging the Caribbean nation into a spiral of instability it has yet to recover from.

It seems that whenever bullets fly in a new conflict, the crisp cadence of Colombian Spanish is never far behind.

So what drives the world’s warlords to seek out Colombians over recruits from neighboring Ecuador or Venezuela, or anywhere else? Combat experience is perhaps the most decisive factor. Colombia’s armed forces are among the most battle-tested in the world, shaped by more than five decades of continuous conflict against FARC—from its emergence in 1964 until the 2016 peace accord—alongside ongoing operations against the offshoot ELN. During those years, Colombian soldiers rotated through live counterinsurgency campaigns in dense jungle terrain, gaining sustained exposure to ambush warfare, intelligence-driven operations, and prolonged combat rather than short, conventional deployments. When those soldiers retire early—often in their 40s, with modest pensions and limited economic prospects—they become prime targets for security firms seeking disciplined, battle-hardened personnel at relatively low cost.

Yet experience and socioeconomics alone do not explain the scale of the phenomenon. Beyond Colombia’s socioeconomic realities and violent history lies a more deliberate engine: the rise of a small network of motivated and morally bankrupt organizers who exploit this reservoir of veterans, converting hard-earned military expertise into a commodity for foreign wars.

This week, the US Department of the Treasury identified several of these organizers when it introduced sanctions against four Colombian individuals and four entities responsible for recruiting former Colombian soldiers for the war in Sudan.

The Treasury’s press release details a complex multinational corporate structure with entities in Colombia, Panama, the United States and the United Arab Emirates that are used to recruit, train, transport, equip, and ship Colombian men to the frontlines of Darfur. According to the release, this venture is headed by Álvaro Andrés Quijano Becerra, a former Colombian military Colonel who resides in Dubai, and Mateo Andres Duque Botero, a Colombian-Spanish businessman.

The Businessman

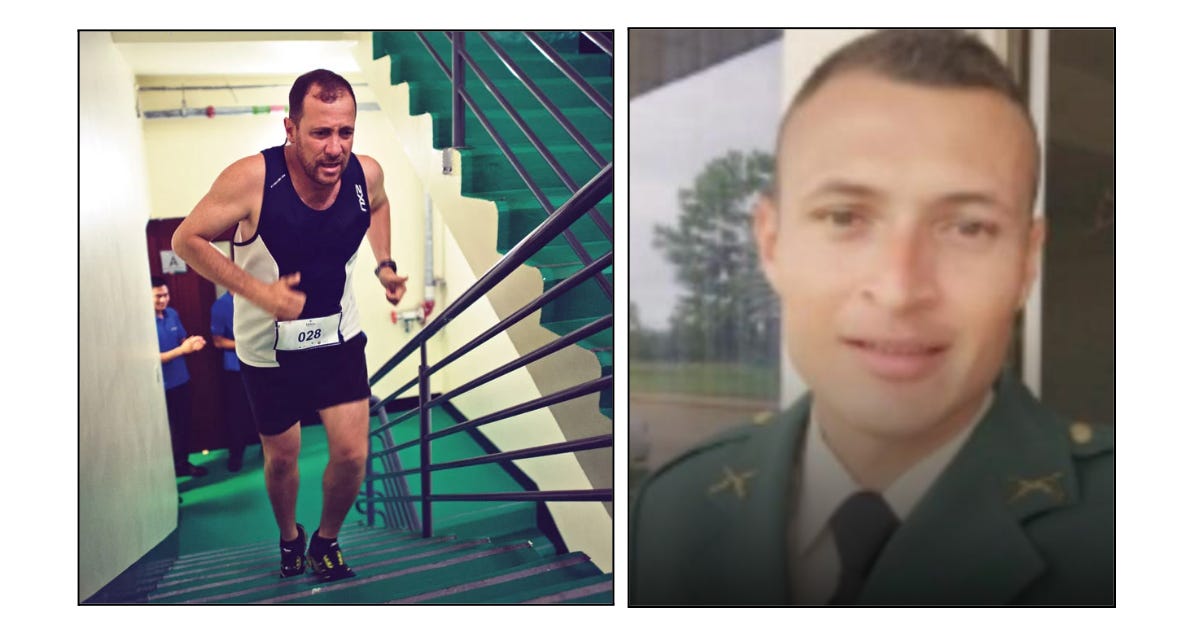

The luxurious Dubai life of Quijano and his wife & business partner, Claudia Viviana Oliveros Forero, appears to be split in equal measure between training for the city’s latest overpriced marathon and coordinating the recruitment of hundreds of drone operators, artillerymen, and snipers for one of the most ruthless militias on Earth—whose massacres in late October were so catastrophic that satellites picked up the bloodstains left behind from space.

Quijano has lived an eventful life. Colombian newspapers report that he was dismissed from the Colombian special forces in 2007 after he was arrested on suspicion of providing information and training members of the Notre del Valle Cartel. Quijano was tried alongside several other military officers in 2009, but a guilty verdict was not reached.

Archived military tribunal documents indicate he was also investigated on suspicion of murder at this time. Public details regarding the outcome of this case are scarce, and its result is unclear.

Following the trial, Quijano relocated to Dubai where he is reported to have joined the Seventh Special Forces Brigade with the UAE military. The experienced Quijano appears to have risen the ranks quickly, becoming a commander of one of the brigade’s foreign fighter battalions.

While serving the UAE, Quijano reportedly began a relationship with Emirati private military firms Global Security Service Group and Al Masar Recruitment Services to bring men into the foreign brigade. Despite his cartel linkages and past arrest, Quijano was able to register as a private security professional with the Colombian government in 2020, and was able to legally recruit Colombians on his own accord for private security positions in the UAE—he was not, however, granted a license to recruit soldiers for missions in Sudan.

According to reporting from Colombian outlet La Silla Vacia, after purchasing a firm in 2022 known as International Services Agency (A4SI), Quijano ramped up the recruitment of former Colombian soldiers. Many of these men report that they were duped into signing contracts to protect oil infrastructure in the Middle East, and did not realize they would be sent to the hellish frontlines of Sudan.

The Staff

Evidence of Quijano’s efforts has trickled onto the feeds of social media sites in the last two years as videos have emerged depicting Spanish speaking men fighting, and dying, in the sand swept streets of Sudan.

Reports from major news outlets indicate that after getting to RSF-controlled Sudan, often via Chad or Libya, these mercenaries train soldiers—including children as young as 12—and engage in offensive missions against the Sudanese military.

Colombian losses are beginning to mount. In August, the Sudanese military reported that it successfully struck a RSF plane loaded with Colombian mercenaries on the tarmac of Nyala Airport in Darfur, killing at least 40. The incident was shocking and led the Colombian President Gutavo Petro to issue a rare, and embarrassing, apology to Sudan. Although Petro vowed to end the scourge of mercenarism his country has unleashed, reports indicate Colombian fighters are still trickling into the combat zone. While the ultimate source of these men’s salaries remains opaque, all roads lead to Abu Dhabi as the Emirates have been exposed for consistently financing the RSF in return for Sudan’s blood gold.

The Alternative Worksite

Ambitious former soldiers have an alternative to the massacre-ridden Sudan however —Ukraine. Up to 2,000 Colombians have signed on to support the Ukrainian side as the country’s access to able-bodied men dwindles, and several hundred have been documented fighting in the country over the last two years.

While contractors hired by Ukraine may be less likely to face arrests from the International Criminal Court compared to their counterparts in the employ of the RSF, fighting for Ukraine has its own host of challenges. Chief among these is the incredibly dangerous nature of the conflict. As showcased by the award-winning film 2000 Meters to Andriivka, the trench-strewn battlefields of the Donbas are the most deadly acres of land on Earth, and every inch of territory gained comes at an immense human toll. Hundreds of Colombians are estimated to have perished or suffered serious injury in the war so far, and while exact statistics will likely never be taken, social media posts have depicted dozens of memorials in Western Ukraine to the Colombian men who gave their lives to the cause—or at least to the paycheck accompanying it.

Those lucky enough to survive the cold trenches of the front have aired various other grievances with their employer, alleging underpayment, racism, and poor support from the Ukrainian units supposedly there as equal partner forces. PTSD is not the only demon haranguing returning Colombians however, as two soldiers who served Ukraine were arrested in Venezuela on their journey home, and deported to Russia by Maduro. In Russia they will not be treated as regular POWS, and are likely to face lengthy prison terms or to be disappeared entirely.

Unsurprisingly, Russia has Colombians of its own. According to Ukraine’s Main Intelligence Directorate, Colombian mercenaries are not only fighting on the Russian side of the conflict, but have committed war crimes on its behalf near the recently seized city of Pokrovsk.

The mindset of the mercenary reveals a dark side of masculinity and humanity alike. While war is often portrayed as a crusade of ideologues—a great clash of human wills—in reality it is frequently little more than a male-dominated work site: a place to pass time, collect a paycheck, climb out of debt, or trigger the occasional dopamine rush. Global conflicts have become a sanctuary for Colombia’s lost and desperate men, and if conditions at home fail to improve, the mercenary path will not merely persist but will continue to draw them in.