Is Georgia Headed for its Own Euromaidan?

Protests are raging in Georgia as its Parliament pushes ahead with a controversial proposal

Written by Felipe Branner, from the ground in Tbilisi

The streets of Georgia’s capital, Tbilisi, are engulfed in protests against the reintroduction of what some call “The Russian Law”, due to its apparent inspiration from a similar law implemented in Putin’s Russia. The bill would label civil society NGOs and media groups receiving more than 20% of their funding from abroad as “agents of foreign influence”. In response, tens of thousands of protesters have taken to the streets and brawls have broken out between parliamentarians in the Georgian national assembly.

Georgia’s ruling party, The Georgian Dream, is relentlessly pushing ahead with the extremely controversial foreign agent law. The government cites the bill as a vital measure to regain sovereignty of their country, which is increasingly becoming a chess piece of international great power politics. Critics, on the other hand, view the law as an emulation of the 2012 Russian foreign agent law, which they argue has been used to stigmatize NGO’s and target opposition organizations. In Russia’s case, the law was later expanded to also include individuals, enabling the Kremlin to crack down on dissident voices objecting to Putin’s political line.

The new bill presents an unprecedented paradox in Georgian politics, as the population is predominantly pro-Eu, with surveys indicating 80% of Georgians wish for their country to expand ties with The European Union. To add to this, the country is still recovering from the national trauma that was the 2008 Russian Invasion of Georgia, a painful scar etched into the collective conscience of the nation. With almost 20% of the country still under de-facto Russian control, through separatist groups in the break-away regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, a profound tension clouds the Russo-Georgian relationship. So what then explains this sudden stroke of seemingly Russian-friendly behavior on part of the Georgian government?

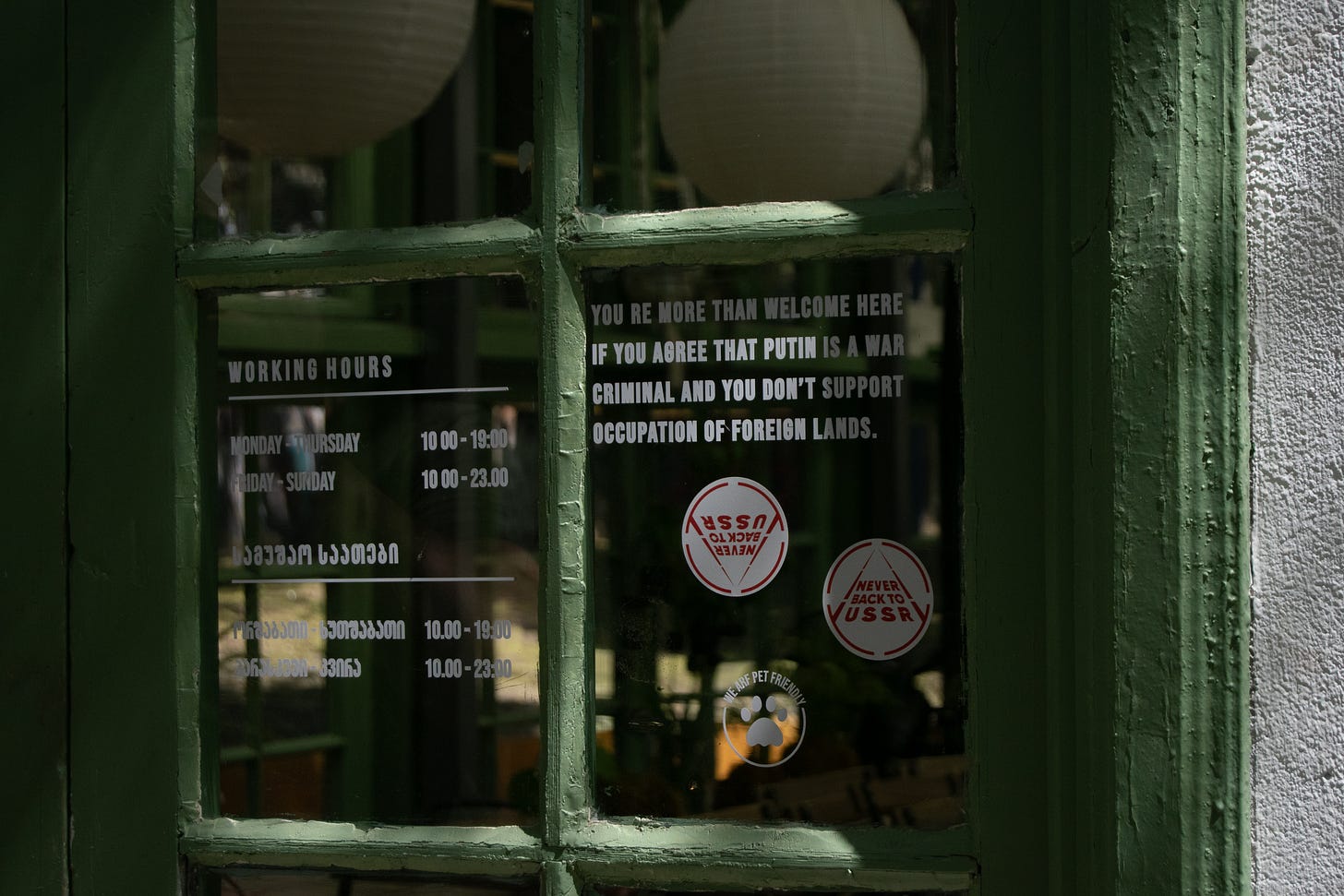

Nowhere is this tension better expressed than on the graffitied walls of Tbilisi, where anti-Russian slogans such as “Russia is a terrorist State”, and “F**k Putin” serve as omnipresent reminders of Georgian animosity towards their towering neighbor. To any outside observer, this does not seem like a national climate where any Russian-sympathetic law could be possible.

Georgia’s Path to the Precipice:

To make sense of this paradox, and the driving forces behind the current controversy, it is essential to analyze the ruling party in Georgia, The Georgian Dream (GD), and how it came to dominate Georgia’s parliament.

The origin of GD can be traced back to the tumultuous first decade of the millennium, a period of tremendous political change in Georgia. Georgia ousted its notoriously corrupt president Eduard Shevardnadze in the 2003 Rose Revolution. Upon his removal, a new era beckoned in Georgian politics, led by the opposition party United National Movement’s (UNM) founder Mikheil Saakashvili, who promised closer ties to the West, crack-downs on corruption, and last but not least, a tougher stance on Russia. This whirlwind of change, though lauded by Western leaders, was, however, not without its challenges. In 2008, Russia, seeing its influence waning in its southern neighbor, decided to mount a full-scale invasion of the country’s north in support of the break-away regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

Saakashvili received much criticism for causing this escalation. His crack-downs on corruption were, too, not without controversy. Shortly before the 2012 parliamentary election, a video surfaced, showing prison inmates being sexually assaulted and undergoing other means of torture in the country’s prison system. This caused massive public outrage in the Georgian populace and played right into the hand of Bidzina Ivanishvili, founder of GD, and the main political rival of Saakashvili’s UNM party. Ivanishvili himself is one of Georgia’s richest men, and is by several accounts said to have close ties to Russia, due to many of his business operations being located there. Saakashvili promptly fled into exile in Ukraine.

Narrowly defeating Saakashvili in the 2012 parliamentary election, GD has gone on to radically reform the country in its image, however, its russia-sympathetic course was not evident at first. Following the pro-EU stance of much of the Georgian populace, its government signed a EU association agreement in 2014. A status-quo can be said to have persisted the following years with some reforms being made by GD into areas such as universal healthcare.

On a warm summer evening on June 20th 2019, Georgia’s pro-European status quo was upended.

Later dubbed as Gavrilov’s night, Russian MP Sergey Gavrilov, on an inter parliamentary delegation to Georgia, delivered an inflammatory speech in Russian, from the chair of the speaker in the parliament of Georgia. This sparked massive protests, as the Georgian public saw his rhetoric as a direct attack on Georgian sovereignty. Calls for a full resignation of the government were demanded by the opposition.

“I face the choice today: either live in a Russian province or as an immigrant. I don't want to make that choice. That’s why I stand here” -Shota Digmelashvili, Activist

The demonstrations were put down with excessive force by the riot police, who justified their tactics by claiming the protesters’ attempted storming of the parliament building called for drastic measures. This event marked a fundamental change in Georgian foreign policy away from the West, and towards a more Russia-sympathetic stance.

With the country increasingly tense and political cleavages drawn up, this climate was further exacerbated by what the opposition has denounced as massive voter fraud in the 2020 parliamentary election, where GD won again with almost 60% of seats. The country’s new prime minister Irakli Garibashvili proceeded to arrest the leader of the largest opposition party UNM at their headquarters. UNM’s Nika Melia was taken in on the counts of inciting violence and agitating to take over the parliament on the aforementioned Gavrilov’s Night. An agreement mediated by European Council President Charles Michel in April 2022, with the support of almost all parties, provided amnesty and a presidential pardon for Nika Melia. However, GD soon after withdrew from this agreement, marking again a further step towards increasing autocratization of the party.

On the eve of local elections in 2021, former president Mikheil Saakashvili returned from his exile abroad. As he was convicted in-absentia to six years in prison on counts of abuse of power, and on entering the country, he was promptly arrested. A hunger strike on his behalf has followed, where an alarming video emerged showing him being violently transferred to a prison-hospital. According to some sources, he is being refused proper healthcare and transfer abroad to more advanced facilities for treatment.

A War to the West

Parallel to this political tumult, stands Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Despite dozens of nations responding to this unprecedented incursion, GD has sported a cautious approach towards the conflict, refusing to implement any sanctions on the Russian regime. Arguably, this can be seen in the light of a country playing a dangerous pragmatic, but perhaps necessary game of balancing Russia on one hand, and the EU on the other. However, this cautious approach has again been met by wide-spread protest on part of Georgians in support of Ukraine, who feel a shared link between their two experiences in the light of the 2008-war.

Further criticism of the Georgian Government’s response has come directly from Ukrainian President Zelenskyy, who withdrew his ambassador from the country in protest in March of 2022. Fast-forward to the present day and GD has been employing many of the same tactics used by Hungary’s Viktor Orban in his approach to Ukraine, with GD increasingly using the term “war-party” for those in the opposition calling for a stronger stance on Russia, ostracizing them as war-hawks putting the country in danger, further polarizing the populace as seen in Hungary.

Last year, when the first draft of the “Russian law” was presented to parliament, massive protests were sparked in Tbilisi, forcing the government to reluctantly delay the law. However, as mentioned earlier, this law is now back on the table.

How The Georgian Dream Maintains Power

Thus the question persists of how a party such as GD, surrounded by controversy, facing an overly EU-friendly population, could garner such popular support at elections and continue down a Russian-friendly path? I attribute this to three factors; polarization of the Georgian voting base, Hungarian-style populism, and the opposition's evident lack of a unifying figure.

GD can be said to “polarize and conquer”, by exacerbating already existent political cleaves in the country, such as those that exist between a moderate, liberal and at times progressive electorate in the bigger cities, and a predominantly conservative and marginally more pro-Russian electorate in the country’s rural areas.

GD has, through increasingly government-controlled media outlets, employed many of the same strategies perfected by Orban’s Hungarian Fidesz-party. These count, framing GD as a staunch defender of traditional ‘Georgian’ values, such as promoting the nuclear family, against disruptive “progressive” forces, and causing a breakdown of law and order in the country. By appealing to traditional family values GD, also counts on the support of the Georgian Orthodox church and its powerful Patriarch, that even supported GD’s campaign in 2012, and legitimizes the party’s rule further in the eyes of the conservative electorate.

The political parliamentary opposition to GD remains utterly divided, without a unifying force to assume the mantle of leader. With Saakashvili in prison, and deeply unpopular with many Georgians, there does not seem to be any potential candidate in waiting.

A Country at the Crossroads

This leaves us where we started, at the massive protests engulfing Tbilisi in the face of the proposed “Russian-law”. Georgian parliamentary elections are coming up in October, and observers see this a potentially key moment to show whether current protests carry a mobilizing effect into the fall on parts of the electorate, especially the young who are vehemently anti-GD and incredibly pro-Europe, a staggering 93% of whom are in favor of Georgia joining the EU. In a country with an average electoral participation rate around 50% and about a million votes required to gain a super-majority, the young vote can be a key factor in determining the result of the coming election - if these protests succeed at mobilizing it.

However many Georgians also fear that the current protests could turn violent, potentially leading to a monumental clash between opposing forces in Georgian society, as the energized pro-European side rallies against a marginally Russian-sympathetic side. If recent history reveals anything, spiralling unrest would likely have major geopolitical consequences. Would we see Russia asserting itself by military intervention in the event of a Georgian Euromaidan-style clash between pro-EU and pro-Russian interests? Would the West, and more importantly the EU, stand firm in the event of such a development, perhaps learning from its past mistakes in Ukraine? Suffice to say, much is at stake in Georgia as the eyes of the world’s great powers descend their gazes upon the tiny Caucasian country.

Photos From Tblisi, by Felipe Branner