How did Mexico go from 'The War on Drugs' to 'Hugs, Not Bullets'?

In 2006, the newly elected Felipe Calderón declared that the cartels represented an existential threat to Mexico; and thus he declared a War on Drugs. Despite deploying around 45,000 troops during his six years in power, the homicide rate in Mexico had tripled, and in 2018, Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) declared an end to the War on Drugs, advocating ‘hugs, not bullets’ to combat narco-terror1-2. So, what went wrong, and how can Mexico learn from its past mistakes to reduce the cartels’ influence moving forward?

Prelude to the 2006 War on Drugs

"The origin of our violence problem begins with the fact that Mexico is located next to the country that has the highest levels of drug consumption in the world. It is as if our neighbor were the biggest drug addict in the world.3"

These were the words of Felipe Calderón in 2010, blaming America for Mexico’s cartel problem, and historically speaking, his thesis certainly carries weight. Mexico’s history of smuggling began during the prohibition era in America, but it skyrocketed during the 1960s and 70s, when demands for cannabis in the States surged4. Mexico’s ‘golden triangle’ of Sinaloa, Chihuahua, and Durango has a perfect climate for cannabis cultivation, and with lots of rural poverty and a weak jobs market, producing and selling the (then) illicit substance was a lucrative option for many. Combined with a long border with America, Mexico supplied the USA with the majority of its cannabis up until legalisation; with around 67% originating from south of the border5. Facing a moral panic, in 1969 Richard Nixon announced a War on Drugs, and this led to active American involvement in combatting cannabis cultivation and smuggling. The war was to last decades, and arguably persists to this day.

In the 1970s, Mexican cartels shifted from cannabis to assisting Colombian cartels in smuggling cocaine to America6. The newly-formed DEA got involved in combating narco-trafficking, assisting their Mexican partners on the ground. Initially, they played a limited advisory role, but this changed when DEA agent 'Kiki' Camarena, depicted in 'Narcos, Mexico,' was brutally murdered by the Guadalajara Cartel in 19857. This event gained national attention in America, and President Ronald Reagan, who also ran a vehemently anti-drugs campaign on a national level, gave government backing to the DEA to actively pursue Camarena’s killers. A 4-year manhunt for Guadalajara Cartel leader Miguel Gallardo led to a reformation of Mexican cartels for increased agility and reduced vulnerability to American interference. Previously, Gallardo’s Guadalajara Cartel had united with almost all major Mexican cartels, but Gallardo decided to splinter operations. He broke up his large cartel into several smaller ones so that their operations were harder for the DEA to track, and that lesser-known drug lords could command operations more. In 1989, Gallardo was arrested, and sentenced to life in prison, but the hope that capturing the ‘kingpin’ would lead to the rest of the body falling turned out to be false. As the cartels were smaller, there was much more competition - for territory, weapons, and money8. Mexico’s cartels restructured their cocaine business - previously, they had merely been traffickers, but they began to purchase the cocaine directly from the Colombian cartels, and sell it themselves9. This saw their power, and their profits, soar.

'Kiki' Camarena's death was front page news in Time Magazine. Source - https://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19881107,00.html

Calderón, and the War on Drugs

After the 1989 capture of Gallardo, America felt that they had avenged Camarena’s death, and their active involvement in Mexico entered a lull. The Mexican government tolerated the cartels, partly out of fear of violence in combatting them, and partly due to many in government being bribed, or threatened, by them10. This changed when Felipe Calderón was elected in 2006. Calderón was elected with just 36.7% of the vote - the lowest ever for a Mexican President, and his opponent AMLO lost by just 0.69%. AMLO protested the result vociferously, claiming there were large irregularities, and Calderón was barely able to complete his oath of allegiance before brawls erupted between his party and the opposition11. There are many Mexican commentators who state that Calderón started the War on Drugs to gain immediate legitimacy, and there are others who state that Calderón viewed the cartels as having infiltrated every level of governance in Mexico, and being an existential threat to the country12. The one thing that the majority of experts agree on, however, is that the war was improvised - with no proper diagnosis of the gravity of the issues, no long-term plan for success, no key metrics against which the plan’s success would be measured, and no consideration of the human cost13. What was unique about Calderón’s decision was that it was the first time a Latin American government took the initiative to combat narcotraffickers, with America providing support, rather than the other way around. In 2008, the Merida Initiative was signed, in which both countries agreed to increase co-operation, and America provided around $3bn to the campaign; a paltry sum compared to Mexico’s $54bn contributed between 2007-1614,15.

Felipe Calderon in military uniform. Credit - https://www.banderasnews.com/0701/edat-militaryalignment.htm

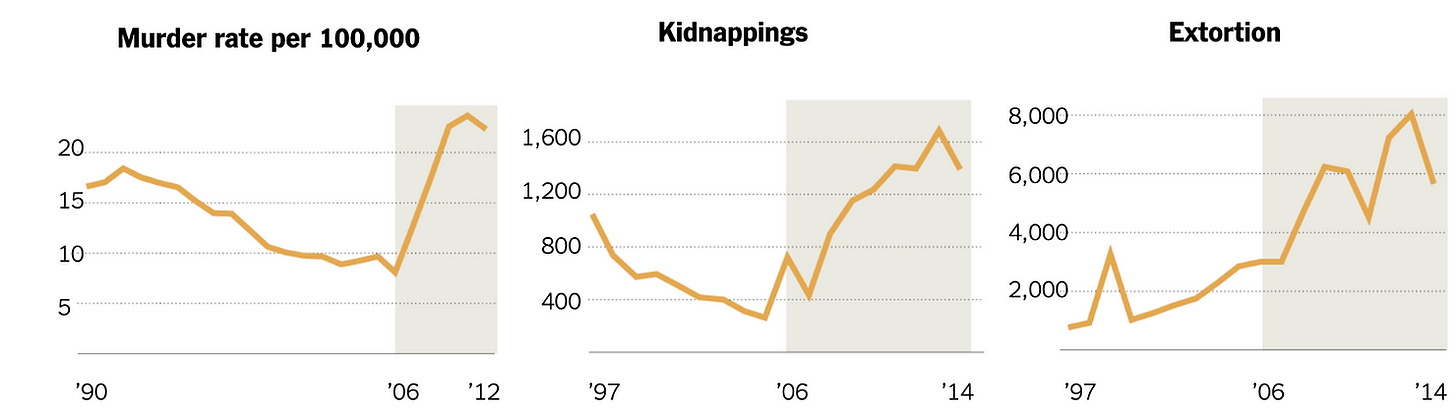

The War on Drugs began in earnest with Operation Michoacan - Calderón’s home state, and at the request of the governor of Michoacan, who pled for help against narcotraffickers whom he accused of making the state ‘ungovernable’16. Calderón sent the military, rather than relying on the Mexican police, as he perceived them to be incompetent - at best - and at worst, corrupt, and loyal to the narcos. This had initial success, with Calderón himself stating in mid-2007: “In the state of Michoacán, for example, the murder rate has fallen almost 40 percent compared with the average over the last six months. People’s support in the regions where we are operating has grown, and that has been very important.17”. Emboldened by the initial success, Calderón expanded the war in 2008 - taking the war nationwide and focusing especially on the border states, as well as Sinaloa, Guadalajara, and Tierra Caliente. One tenet of the plan was the ‘Kingpin Strategy’ - that is, to target the leaders of the cartels, in the belief that should the head be cut off, the body will fall. This was the strategy used in taking down Pablo Escobar in Colombia, and the DEA prescribed it for the Mexican War on Drugs as well18. It achieved its aims - towards the end of his six years in power, Calderón regularly boasted of his achievement of having eliminated around two-thirds of the most wanted kingpins in Mexico19. This was true, however, it ignored the fact that the cartels had splintered and become much more violent - with the murder rate increasing almost fivefold during his tenure20. Public opinion began to turn after the Salvarcar Massacre - a massacre in which 16 youths were killed in a case of mistaken identity. Calderón initially stated that the youths were gang members, provoking an angry response from the public, and many interviewed said that it was typical of Calderón’s flippant attitude towards the collateral damage caused by heavy-handed military intervention.

Why the war on drugs failed

Calderón had to rely on the military so much as he believed that he could not trust the Mexican police. As Jorge Casteñada, Mexico’s ex-Foreign Secretary remarked “[the police] work for the drug cartels — and everybody in Mexico knows that. Clearly, you can’t ask them to fight the drug cartels because they are part of the drug cartels22”. Calderón aligned himself with the military from day one - appearing in military uniform early on in his tenure, and he utilised 45,000 soldiers during his tenure23. This had its own issues however; as Human Rights Watch slammed the Mexican military for participating in numerous rapes, killings, tortures, and forced disappearances, and they note that “In [five states], military prosecutors opened 1,615 investigations from 2007 to April 2011 into crimes allegedly committed by soldiers against civilians. Not a single soldier has been convicted in these cases”24. The military’s deployment was thus deeply unpopular amongst Mexicans, and its bad reputation was compounded by Genaro García Luna’s arrest and conviction. Luna was the Secretary of Public Security during Calderón’s rule, and founded the ‘New Police Model’, and yet in 2019, it emerged that he had taken $3m in bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel25. This epitomised the corrupt nature of the Mexican authorities and explains why they were not able to defeat the narcotraffickers.

Kingpin Strategy

Perhaps the biggest reason the war on drugs failed was the ‘Kingpin Strategy’. As the Modern War Institute notes, “After leadership arrests or deaths, large organizations splinter, new groups emerge, and existing organizations expand into new areas. The result is a violent scramble for territorial control”, and “more criminal groups means more potential fronts of conflict”26. The Kingpin approach also failed in Colombia, leading to a spike in violence after Pablo Escobar was toppled, and as Jane Esberg, fellow at the Stanford Centre for International Conflict and Negotiation states, “With more than two hundred groups now operating in the country, it is not entirely clear what a true kingpin strategy even looks like today.27” Indeed, as cartels fracture, a scramble for power and territory emerges, which leads to a violent, deadly competition for resources. This in turn leads to an increase in kidnappings of locals, extortion, and murder, in order to obtain as much money, territory and resources as possible to fill the power vacuum.

Mexico's violence spiked after the 2006 War on Drugs. Credit https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/02/16/world/americas/mexicos-kingpin-strategy-against-the-drug-cartels.html 28

Outlook to the future

In 2018, AMLO declared that the war on drugs had failed and was over, promising a policy of ‘Hugs, not bullets’29. This was popular, and saw him win a landslide - possibly because Mexicans did not believe ‘fighting fire with fire’ could work, and possibly because they were simply tired of the constant violence. AMLO has taken a much more peaceful, conciliatory approach to the cartels, stating that he would support a peace agreement with them, and saying that the cartels’ strength comes from poverty, a weak labour market for youths, and a lack of education30. There has been a small decline in the murder rate since AMLO took charge, and with Claudia Sheinbaum, who vehemently opposed the war on drugs, likely to succeed AMLO next year, an imminent return to the tactics used by Calderón looks unlikely31-32. Aside from there not being the political will to combat the narcos, it is a dangerous business - with Mexico seeing one of the world’s highest rates of politically motivated assassination for both candidates and journalists33. Further, the cartels do not just deal in drugs these days - their tentacles have infiltrated most areas of Mexico’s economy - from human trafficking, racketeering, to the avocado trade34.

It seems that, for now, the Mexican political establishment has no desire to combat cartel violence - a problem endemic to all of Latin America, and one that is worsening. Perhaps AMLO’s diagnosis of the root causes of cartels is correct, and Mexico’s only escape from the influence of the cartels is to improve the economy, and education. In a glimmer of hope, Mexico has seen a sharp increase in the number of students completing university degrees, and their economy is performing the best in Latin America35-36. It is important to remember that the drug epidemic not only affects Mexico, but its neighbour north of the border too. With Mexico registering nearly 30,000 murders last year, and the USA registering 110,000 deaths due to overdose, with the majority of the drugs involved being trafficked from Mexico, the human cost to this policy failure is enormous37-38. Just because there is a problem, however, does not mean that there is a solution, and it appears that both Mexico and the USA have tried and failed in all of their approaches so far. Pablo Escobar’s prediction “[that] in the long run, in the future, cocaine will tend to be legalized” might come to fruition out of an absence of any alternative, although perhaps not with full legalisation, but rather decriminalisation39. Decriminilisation has become more and more popular lately, with progressive governments in Oregon State, Portugal, and Berlin treating users as victims and addicts, rather than criminals. As Daniel Raisbeck, writer for ‘Foreign Policy’, and Latin American policy analyst notes, “legalisation would be the least-worst option for Latin America”40. It could be the only way to end the decades old drugs war that has caused so much death and destruction in all of the Americas, as all other options have been tried and exhausted.

What did you think of the article? Let us know in the comments!

Sources:

1 - Mexico murder/homicide rate 1990-2023 (no date) MacroTrends. Available at: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/MEX/mexico/murder-homicide-rate#: (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

2 - Minns, E.P.J. et al. (2023) ‘Hugs, not bullets’: Government policy and cartel violence in Mexico, Australian Institute of International Affairs. Available at: https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/hugs-not-bullets-government-policy-and-cartel-violence-in-mexico/ (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

3 - Carlson, B. (2013) Quote of the day: Mexican president blames violence on ‘drug addict’ U.S., The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2010/06/quote-of-the-day-mexican-president-blames-violence-on-drug-addict-u-s/345192/ (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

4 - Vulliamy, Ed. Amexica: War Along the Borderline. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010.

5 - Where does pot come from: Domestic Growers or Mexican cartels? (2018) KJZZ. Available at: https://kjzz.org/content/8319/where-does-pot-come-domestic-growers-or-mexican-cartels (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

6 -Drug cartel (2023) Encyclopædia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/drug-cartel (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

7 - Bancroft, M. et al. (no date) Kiki Camarena, the Guadalajara Cartel, and the start of an International Drug War, Perspectives on Black Markets v 4. Available at: https://iu.pressbooks.pub/perspectives4/chapter/kiki-camarena-the-guadalajara-cartel-and-the-start-of-an-international-drug-war/ (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

8 - IBID

9 - (No date) How democracies emerge - journal of democracy. Available at: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Berman-18-1.pdf (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

10 - Inside Mexico’s Drug Wars (no date) Modern latin america. Available at: https://library.brown.edu/create/modernlatinamerica/chapters/chapter-3-mexico/moments-in-mexican-history/inside-mexicos-drug-wars/ (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

11 - Chaos erupts as Mexican president is sworn in (2006) The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/dec/02/mexico (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

12 - La guerra improvisada: los años de Calderón y sus consecuencias, Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, Tony Payan, Oceáno, 2021

13 - IBID

14 - Mexico’s War on Drugs: What has it achieved and how is the US involved? (2016) The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2016/dec/08/mexico-war-on-drugs-cost-achievements-us-billions (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

15 - Has the mérida initiative failed the U.S. and Mexico? (2021) The Dialogue. Available at: https://www.thedialogue.org/analysis/has-the-merida-initiative-failed-the-u-s-and-mexico/ (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

16 - La guerra improvisada: los años de Calderón y sus consecuencias, Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, Tony Payan, Oceáno, 2021

17 - https://www.ft.com/content/317c1bbc-ab01-11db-b5db-0000779e2340

18 - Chase, I. (2022) The kingpin strategy: More violence, no peace, SHOC RUSI. Available at: https://shoc.rusi.org/blog/the-kingpin-strategy-more-violence-no-peace/ (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

19 - Peña Nieto team decries past drug cartel strategy - and keeps it (2012) Los Angeles Times. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/world/la-xpm-2012-dec-21-la-fg-mexico-kingpin-20121222-story.html (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

20 - (No date) Justice in Mexico. Available at: https://justiceinmexico.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Organized-Crime-and-Violence-in-Mexico-2019.pdf (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

21 - Ciudad Juárez: Mexico’s nameless dead | Luis Hernandez Navarro (2010) The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/nov/09/ciudad-juarez-mexico-drugs-war (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

22 - Mexico’s Failed Drug War (no date) Cato.org. Available at: https://www.cato.org/economic-development-bulletin/mexicos-failed-drug-war (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

23 - Some Question Mexican Leader’s Public Alignment with Military (no date) Some question Mexican leader’s public alignment with military. Available at: https://www.banderasnews.com/0701/edat-militaryalignment.htm (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

24 - Neither rights nor security (2023) Human Rights Watch. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2011/11/09/neither-rights-nor-security/killings-torture-and-disappearances-mexicos-war-drugs (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

25 - Ex-mexican secretary of public security Genaro Garcia Luna convicted of engaging in a continuing criminal enterprise and taking millions in cash bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel (2023) Eastern District of New York | Ex-Mexican Secretary of Public Security Genaro Garcia Luna Convicted of Engaging in a Continuing Criminal Enterprise and Taking Millions in Cash Bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel | United States Department of Justice. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/usao-edny/pr/ex-mexican-secretary-public-security-genaro-garcia-luna-convicted-engaging-continuing (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

26 - Esberg, J. (2022) Why Mexico’s kingpin strategy failed: Targeting leaders led to more criminal groups and more violence, Modern War Institute. Available at: https://mwi.westpoint.edu/why-mexicos-kingpin-strategy-failed-targeting-leaders-led-to-more-criminal-groups-and-more-violence/ (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

27 - IBID

28 - Mexico’s kingpin strategy against the Drug Cartels (2016) The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/02/16/world/americas/mexicos-kingpin-strategy-against-the-drug-cartels.html (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

29 - Mexico’s president under pressure over ‘hugs not bullets’ cartel policy (2019) The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/nov/05/mexicos-security-failure-grisly-cartel-shootout-shows-who-holds-the-power (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

30 - Mexico’s president says he would support peace agreement with cartels (2023) The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/31/mexico-president-peace-agreement-cartels (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

31 - “Mexico Murder/Homicide Rate 1990-2023 | MacroTrends.” Macrotrends, https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/MEX/mexico/murder-homicide-rate. Accessed 31 October 2023.

32 - “Claudia Sheinbaum se manifestó en contra de "la guerra del narco" en la CDMX.” El Economista, 15 April 2018, https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/politica/Claudia-Sheinbaum-se-manifesto-en-contra-de-la-guerra-del-narco-en-la-CDMX-20180415-0014.html. Accessed 31 October 2023.

33 - Trujillo, Teresa Martínez. “Data on Political & Electoral Violence in Mexico, 2020-2021.” Noria Research, https://noria-research.com/data-on-electoral-violence-mexico-2020-2021/. Accessed 31 October 2023.

34 - Carbajal, Braulio. “Corrupción y 'narco' asedian el millonario negocio del aguacate.” La Jornada, 11 February 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/notas/2023/02/11/reportaje/corrupcion-y-narco-asedian-el-millonario-negocio-del-aguacate/. Accessed 31 October 2023.

35 - Hernandez, Valerie. “The Mexican Economy Is the Clear Winner in Latin America in 2023.” International Banker, 9 August 2023, https://internationalbanker.com/finance/the-mexican-economy-is-the-clear-winner-in-latin-america-in-2023/. Accessed 31 October 2023.

36 - Pedraza, Lisdey Espinoza. “Education reforms in Mexico: what challenges lie ahead? | British Council.” British Council | Opportunities and insight, 15 August 2023, https://opportunities-insight.britishcouncil.org/blog/education-reforms-mexico-what-challenges-lie-ahead. Accessed 31 October 2023.

37 - “Mexico Murder/Homicide Rate 1990-2023 | MacroTrends.” Macrotrends, https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/MEX/mexico/murder-homicide-rate. Accessed 31 October 2023.

38 - Mann, Brian. “Fentanyl sparks drug overdose record.” NPR, 18 May 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/05/18/1176830906/overdose-death-2022-record. Accessed 31 October 2023.

39 - Kryt, Jeremy. “Colombia Considers the Ultimate Strike Against Cartels: Legalizing Cocaine.” The Daily Beast, 7 December 2020, https://www.thedailybeast.com/colombia-considers-the-ultimate-strike-against-cartels-legalizing-cocaine. Accessed 31 October 2023.

40 - Quijano, Mauricio J. “Cocaine Legalization is the Least Worst Option for my Native Colombia.” Mississippi Free Press, 25 January 2022, https://www.mississippifreepress.org/20037/cocaine-legalization-is-the-least-worst-option-for-my-native-colombia. Accessed 31 October 2023.