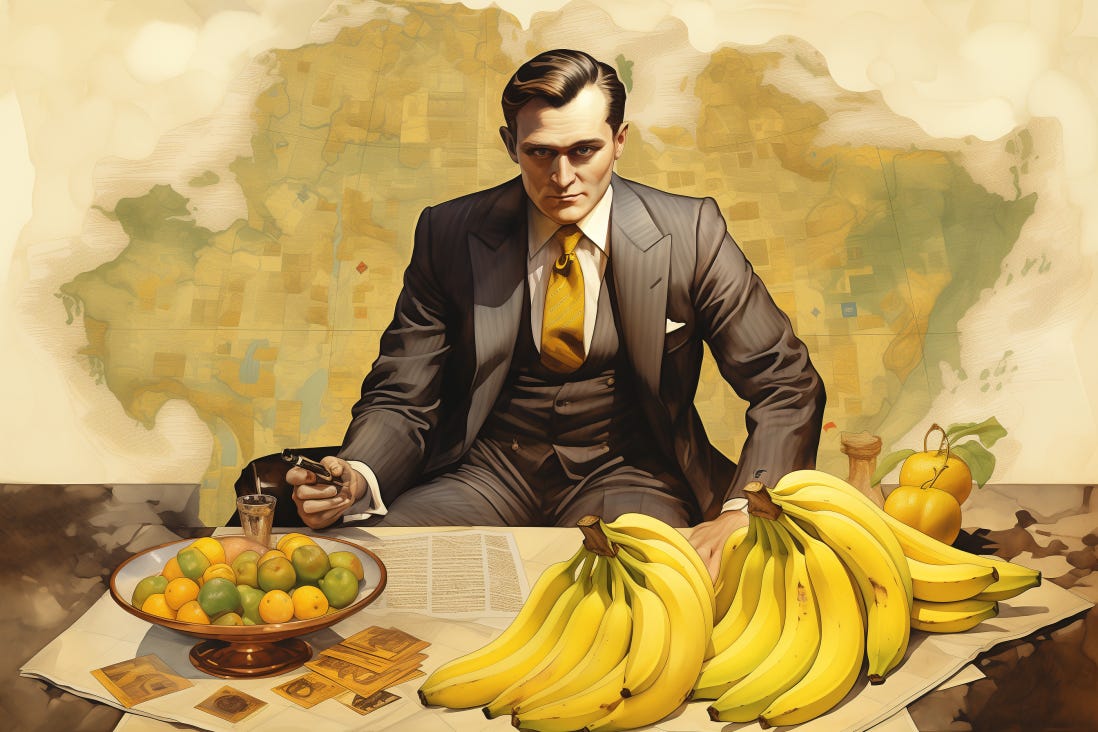

Guatemala: History is Repeating Itself in the Original Banana Republic.

Bernardo Arévalo will seek to take on the kleptocracy, just as his father did.

The term ‘banana republic’ was coined as a specific reference to Guatemala. The central-American country has long been plundered for economic gains by multinational companies, with bananas being their biggest export. The only President in Guatemala’s history who successfully took a stand against the kleptocracy was Juan José Arévalo in the 1940’s, who faced a remarkable thirty coup attempts for his stances. Eighty years later, Guatemala is yet again in the “claws of a pact of the corrupt”, and against this backdrop, Arévalo’s son - Bernardo Arévalo, has been elected as President.

Guatemala - the original banana republic

When in 1900 the United Fruit Company (UFCO) pitched itself to Guatemala as a credible partner for development and modernization, the nation that was once at the heart of the Mayan Empire became a banana republic. Scant of foreign capital, the country with the highest share of indigenous people in Latin America accepted, and in 1900 the government sold over 40% of its cultivable land to UFCO. The fruit conglomerate would end up propping up all of the governments which would follow, and it became impossible to rule without the UFCO’s blessing.

From 1900-1944, Guatemala was governed by a draconian police state, with an ever-increasing land dispossession in favour of the banana exporters. Political repression and harsh labour laws were the norm. In 1944 the discontent with the regime led to a revolution that resulted in the President and his senior entourage fleeing to their real constituents in New Orleans - where the UFCO is headquartered - to live in exile.

Juan Jose Arévalo

The ’10 years of Spring’ followed, after the current President-elect’s father - Juan Jose Arévalo - won around 85% of the votes in Guatemala’s first free and fair elections. Considered by many to be Guatemala’s greatest president, Arévalo set about modernising Guatemala - introducing universal suffrage, freedom of the press, and the formation of political parties (aside from Communists, who were banned). Arévalo allowed workers to organise and form unions and issued the ‘Code of Work’ in 1947 - introducing basic worker rights and protections. State institutions were established, including the Guatemalan Institute of Social Security, the Bank of Guatemala, and access to healthcare and education were widened.

Despite the economy’s growth, and Arévalo’s regime being supported by unions and the middle classes alike, Arévalo’s opposition attempted to thwart progress by tarring him as a communist. The first democratically elected President in Guatemala’s history defined his ideology as ‘spiritual socialism’, which was distinctly different from Marxist-Leninism, and actively opposed the non-democratic methods of the USSR. In spite of this, the powerful Catholic Church staunchly opposed his regime, stating that it was infiltrated by the atheist Russians and threatened family values. The UFCO also opposed his regime, as did the US, not only to support its own big business, but also in the height of the ‘Red Scare’, and as part of the decision to expand the Monroe Doctrine to what it perceived to be its ‘backyard’. There were around thirty coup attempts made against Arévalo, varying in severity, but despite this, he was able to complete his term.

Counter-Revolution

His successor was not so lucky, however. The passage of an agrarian reform which returned uncultivated land to the landless locals was the straw that broke the camel’s back. A CIA-backed coup was sanctioned in 1954, and the junta immediately overturned the agrarian reform and cracked down on opposition.

Following the coup, successive governments used increasingly brutal methods to quell opposition and prop up the land-owning elites. A guerrilla movement against the regime gave rise to the Guatemalan Civil War in 1962, after they attacked the UFCO’s offices, which led to widespread support for the resistance, popular strikes, and a government crackdown - whose heavy-handed response led to a full-blown insurgency movement.

The US government covertly backed and trained the Guatemalan counter-insurgency campaign during the civil war, even during the 1980s when Guatemala became a pariah state due to its atrocities. Eventually, peace accords were signed in 1996, but not before over one million people were displaced, and over 200,000 had been killed.

State capture

In modern history, Guatemala has been beset by corruption, with the country ranking below nations such as Afghanistan and the Central African Republic on the corruption perception index. Crime has risen, poverty is at around 55%, and Guatemalans represent the second largest nationality that crosses the American border. In the face of this, the US now strives to support a politically and economically stable Guatemala in order to halt the migrant flow. Rather than America, the biggest threat to progress in Guatemala has come from the political elites, who have attempted to kidnap state institutions.

In 2015, an investigation into the ‘La Linea’ corruption scandal resulted in the President and Vice-President being arrested and charged. Led by the UN-backed anti-corruption probe (CICIG), and Juan Francisco Sandoval of the Special Prosecutor's Office against Impunity (FECI), it toppled the incumbent government. 28 officials ended up being brought to trial, with both President Otto Molina and Roxana Baldetti being sentenced to 16 years in prison.

After the ‘La Linea’ scandal, Sandoval’s investigations continued, continued to be fruitful - as he uncovered criminal political and economic networks, involving state institutions, judges, politicians and businessmen. Over fifty criminal networks were investigated and brought to justice, and scandals ranged from the revelation that dozens of legislators had been bribed by a mobile network company to pass favourable legislation, to the then-president Jimmy Morales’ campaign having received illicit funding.

The Pact of the Corrupt

Not willing to go down without a fight, those implicated in the investigations and convictions struck back. In 2017, Congress changed the Penal Code so that those found guilty of corruption charges would not face prison. Mass protests ensued, and the opposition termed the alliance between presidents, legislators and businessmen who sought impunity as “the pact of the corrupt” - led by President Jimmy Morales himself.

The appointment of Maria Consuelo Porras - described as “the sword and the shield of the pact” - as Attorney General (AG) in 2018 was another aggressive move by Morales in the fight for impunity. Porras was viewed as unlikely to continue the investigations into corruption, and since she became AG, the Guatemalan institutions have done all in their power to stop any corruption investigations from continuing.

A year later, the head of the CICIG probe, Velasquez, was denied entry into Guatemala, and the probe was shut down. Sandoval and his team continued their investigations, however, and they were not removed initially, due to support from the US, with them recognising him as a “champion in the fight against corruption”. Against the threat of sanctions, the ‘pact of the corrupt’ did not crack down on Sandoval, until investigations into President Giametti allegedly accepting bribes from Russia commenced.

As the investigations progressed, Porras removed Sandoval, and issued an arrest warrant that led to him fleeing Guatemala, “fearing for his life”. Mass domestic protests ensued, and subsequently, Porras was heavily sanctioned by the US, who declared her “an undemocratic and corrupt official”. The witch hunt did not end there, as the AG’s office arrested several other former prosecutors linked to FECI, and many judges, such as Miguel Ángel Gálvez who presided over the La Linea case, fled the country.

The 2023 elections

Against this backdrop, Bernardo Arévalo, son of the only Guatemalan president in the last 100 years to successfully stand up against the interests of the land-owning elites and foreign companies, launched his campaign. Arévalo, of the Semilla party, campaigned with a very small budget, spreading his message amongst young voters on social media. His victory in the first round came as a surprise, and experts say that should it have been more predictable, he would have been barred from running, just as front-runners in 2019 and 2023 were banned. Arévalo’s campaign was focused on transparency, with the promise to have a “specifically anti-corruption cabinet”, and a ten-point plan to decrease fraudulent conduct within the government.

His opponent, Sandra Torres, is very much from the political establishment, having served as First Lady between 2008-2011. She had the support of many mayors, congressmen, and businessmen and has been coined the ‘eternal candidate’ as she has run for president several times. She labelled Arévalo a ‘communist’, and positioned herself as protecting family values, wooing the old forces of Guatemala who were opposed to anti-corruption efforts. She allied with the Evangelical Church, of which 41% of Guatemalans purport to align with, and heavily criticised Arévalo for accompanying his daughter down the aisle at her own same-sex wedding in Mexico.

The ‘Technical Coup’

While Arévalo won the election by a landslide - winning around 61% of the vote to Torres’ 37%, Porras used every trick in the book to attempt to block his transition to President, described as a ‘slow-motion coup’. She attempted to disqualify Arévalo’s party - Semilla - meaning that his legislators would not be able to sit on committees or be in cabinet. She also ordered the raiding of the party’s offices - a move which led Arévalo to briefly withdraw from the transition power, citing “flagrant crimes of abuse of authority for electoral purposes”, and calling it an attempted coup d’etat.

Porras has faced enormous backlash, both in Guatemala and internationally. Since Porras’ coup attempt, intense, daily protests and road blockages have occurred - including a two-week national strike led by Guatemala’s indigenous people, calling for Porras to resign and be brought to justice. The international community’s response has been equally strong - with the US, UK, EU, and Organisation of American States (OAS) all confirming that there were no electoral irregularities.

On 9th December, Porras pulled out all of the stops - declaring the results of the elections invalid and therefore null, despite the time period to contest the elections having elapsed. She also denounced Semilla as a “criminal organisation”, and had three legal causes against Arévalo that could lead to his imprisonment, and convened an extraordinary session of Congress to try to pack the electoral tribunal with magistrates partial to the coup.

Four days later, and after the US sanctioned 100 of the 160 congress members, the coupmongers’ coalition collapsed, and they failed to get enough votes to get their magistrates elected. El País notes that every day, more and more people are abandoning the coup attempt. Individually, most of the Guatemalan political elite have their assets abroad, and with threats to freeze these assets and restrict their travel, supporting the coup could leave many isolated in Guatemala, and penniless. On 14th December, the Supreme Electoral Council ratified the election results, refusing Porras’ petition to annul them.

The ‘drowning kicks of the coup’.

The President-elect defined Porras’ actions as “the drowning kicks of the coup”. El País notes that every day, more and more people are abandoning the coup attempt, as individually, most of the Guatemalan political elite have their assets abroad, and with threats to freeze these assets and restrict their travel, supporting the coup could leave many isolated to Guatemala, and penniless.

The lack of any support for the coup from any nation could leave Guatemala as the most pariah state in the world, as not even Russia, China or Venezuela have come out in support of Porras. For now, it appears likely that the attempt to block Arévalo will not succeed, as both domestic protests and international sanctions would leave Guatemala practically ungovernable. Attempts to subvert his, and his party’s power, however, are ongoing, and even if he becomes President nominally, should his party be disqualified and without a majority in Congress, he might be left a lame duck President.

Room for optimism?

It appears that nearly eighty years after Arévalo senior became president of Guatemala, and ushered in popular social change, Arévalo junior is on the brink of doing the same.

The scale of Arévalo’s mandate, as well as the attempted coup against him, will give the President-elect a very strong mandate to govern, should he take office on January 14th. With a young population, fertile soil and multiple hotspots for tourists to flock to, Guatemala has the potential to grow. They can also rely on the US for support in the fight against corruption, and there could be a spike in Foreign Direct Investment - key for economic development - should Arévalo successfully reduce corruption.

Arévalo Jr. has declared that his job is to follow in his father’s footsteps. He has already faced more challenges before taking the presidency than many presidents faced during their rule. The road ahead will be very difficult - he will have to deal with corrupted state institutions, and no majority in Congress. To enact serious change, he may have to make deals with the corrupt elites that he promised to eliminate. Much like his father, he represents a clear break from the failed experiments of the past, and there is hope that he can win the battle against corruption, and usher in a Second Guatemalan Spring.